What is the NEAP?

The neighborhood effect averaging problem (NEAP) refers to the problem that individual mobility-based exposures to environmental factors tend towards the mean level of the participants or population of a study area when compared to their residence-based exposures. As a result of the NEAP, ignoring people's daily mobility and exposures to nonresidential contexts in geographic or epidemiological studies may lead to erroneous results in the study of mobility-dependent exposures (e.g., noise and air pollution) and their health impact because people's daily mobility may amplify or attenuate the exposures they experienced in their residential neighborhoods. This means that using residence-based neighborhoods to estimate individual exposures to and the health impact of environmental factors may overestimate the statistical significance and effect size of the neighborhood effect.

The NEAP was first identified and described by Kwan (2018), who suggested that "for health

outcomes that are also affected by exposures to environmental factors in people's nonresidential

neighborhoods as they move around in their daily life (mobility-dependent exposures), using

residence-based neighborhoods to estimate individual exposures to and the health impact of

environmental factors will tend to overestimate the statistical significance and effect size

of the neighborhood effect because it ignores the confounding effect of neighborhood effect

averaging that arises from human daily mobility."

How Neighborhood Effect Averaging Occurs

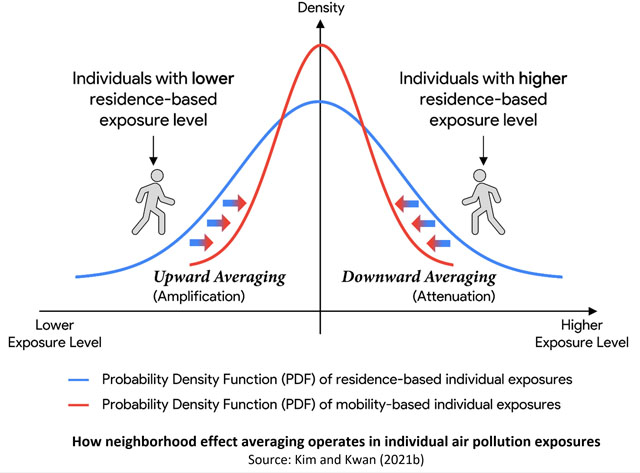

Given that most people move around to undertake their daily activities (e.g., work, attend school, or shop), they are exposed to the environmental contexts of many different areas outside their residential neighborhoods in a day. As a person travels to areas outside his or her residential neighborhood, the person may experience similar or different levels of exposure when compared to that of his or her residential neighborhood. Because of the diversity in the intensity of the environmental factor in question (e.g., air pollution) over space and time in any study area, a person's exposure level in non-residential neighborhoods may be higher, lower, or similar when compared to the exposure level experienced in his or her residential neighborhood.As indicated by several studies, the probability distribution of individual residence-based exposure approximates a bell-shaped distribution, which means that many people have exposure levels around the mean value of the participants or the population of the study area, while fewer people have very high or low exposure levels (Dewulf et al. 2016; Shafran-Nathan et al. 2017; Yu et al. 2018; Kim and Kwan 2020). Therefore, a person who lives in a neighborhood with a high level of an environmental factor (and thus exposure) will tend to visit areas that are more likely to have lower levels of such an environmental factor as a result of his or her daily mobility, while a person who lives in a neighborhood with a low level of the environmental factor will tend to visit areas that are more likely to have higher levels of such environmental factor. For those who have residence-based exposure levels around the mean value, their exposure levels in non-residential neighborhoods tend to be similar to those of their residential neighborhoods, because they tend to visit areas that are less likely to have significantly different levels of such an environmental factor in their daily life, given the bell-shaped distribution of individual residence-based exposures.

As a result, the neighborhood effect assessed with a traditional residence-based approach for individuals whose residence-based exposures are much higher than the mean exposure will be overestimated because these individuals tend to experience lower levels of exposure outside their residential neighborhoods, which attenuates their high exposures in their residential neighborhoods. On the other hand, the neighborhood effect for individuals whose residence-based exposures are much lower than the mean exposure will be underestimated because these individuals tend to experience higher levels of exposure outside their residential neighborhoods, which amplifies their low exposures in their residential neighborhoods. This means that using residence-based neighborhoods to estimate individual exposures to and the health impact of environmental factors might give undue weight to the neighborhood effect, leading to potentially misleading or erroneous results (e.g., underestimating the statistical significance and effect size of the neighborhood effect).

For mobility-dependent exposures (e.g., noise and air pollution), more accurate assessments of people's environmental exposures that take their daily mobility into account (e.g., using GPS tracking and mobile pollution sensors to measure individual real-time exposures) will therefore lead to an overall tendency toward the mean exposure because exposure levels for people whose residence-based exposures are lower or higher than the mean exposure will tend toward the mean exposure, thus moderating the influence of the environmental factor in their residential neighborhoods on their health behaviors or outcomes. This is neighborhood effect averaging, which is a fundamental methodological issue when examining the health effects of mobility-dependent exposures. As both the NEAP and the UGCoP problem are serious methodological problems, and both could lead to significant inferential error in studies on how environmental factors affect human health behaviors and outcomes, it is important to address them in geographic studies to obtain more reliable results.

Evidence on the NEAP

The NEAP was first identified in Kwan (2018) based on recent studies on individual exposures to air pollution (e.g., Dewulf et al. 2016; Yu et al. 2018). To investigate the validity of the notion, Kwan and her associates undertook further studies on individual exposures to traffic congestion, air pollution and other ethnic groups in the U.S. and China. Based on these studies, five subsequent papers provide further evidence for the existence of the NEAP and how its extent is related to the daily mobility of different social groups. For instance, Kim and Kwan (2019) examined whether individual exposures to traffic congestion are significantly different between assessments obtained with and without considering individuals' activity-travel patterns. The study used crowdsourced real-time traffic congestion data and the activity-travel data of 250 individuals in Los Angeles to compare these two assessments of individual exposures to traffic congestion. The results indicated the existence of the NEAP: the distribution of exposures converges towards the average value when individuals' activity-travel patterns are considered (when compared to one obtained when those patterns are not considered). This study is important in that the NEAP was observed even when only part of a person's daily mobility is ignored (by considering only the commute trip).Kim and Kwan (2021a) provide another in-depth examination of the NEAP. The study assessed individual exposures to ground-level ozone using the activity-travel diary data of 2,737 individuals collected in Los Angeles. The study found that the NEAP exists and that high-income, employed, younger, and male participants (when compared to low-income, non-working, older, and female participants) are associated with higher levels of neighborhood effect averaging because of their higher levels of daily mobility. Another study using the same data found that non-workers (e.g., the unemployed, homemakers, the retired, and students) do not experience downward averaging (Kim and Kwan 2020b). This means that non-workers are far less likely to experience downward averaging that could have attenuated their high exposures experienced in their residential neighborhoods while traveling to other neighborhoods (thus, being doubly disadvantaged).

In another study, Ma et al. (2020) used GPS and mobile sensor data to compare the mobility-based and residential-based exposures of 106 participants to air pollution in a high-pollution community in Beijing, China. The study found that most participants experienced the NEAP and could lower their exposure by their daily mobility. However, three social groups with low daily mobility could not avoid the high pollution in their residential neighborhoods: (1) low-income people with low mobility and limited travel outside their residential neighborhoods, (2) blue-collar workers with long work hours at low-end workplaces, and (3) elderly people who face mobility and household constraints.

These four studies on the NEAP are on air pollution exposure. Tan et al (2020), however, examined whether the NEAP exists in a study of ethnic segregation using the notion of segregation as limited exposure to other ethnic groups. The paper conceives a person's exposure to people of other ethnic groups as the person's ethnic exposure, which is used to capture the extent to which he/she experiences ethnic segregation. The study compared the Hui ethnic minorities and the Han majorities in Xining, China using census and activity diary data. It found that the NEAP exists when examining ethnic exposure. Participants who live in highly mixed neighborhoods (with high exposures to the other ethnic group) experience lower activity-space exposures because they tend to conduct their daily activities in ethnically less mixed areas outside their home neighborhoods (which are more segregated). In contrast, participants who live in highly segregated neighborhoods (with low exposures to the other ethnic group) tend to have higher exposures in their activity locations outside their home neighborhoods (which are less segregated). The study further found that specific types of activity places, especially workplaces and parks, are associated with high levels of the NEAP.

Extending research on the NEAP to other realms, Huang and Kwan (2021) examined how assessments of individual exposure to COVID-19 risk are affected by the NEAP and the UGCoP. Using the COVID-19 data on an open-access government website and the individual-level activity data of 60 confirmed COVID-19 cases (infected persons) in Hong Kong, the study represented COVID-19 risk environments using case-based and venues-based high-risk locations. The COVID-19 risk of each of the 60 selected cases is then evaluated by three approaches based on their exposure to the case-based or venue-based risk environments: the mobility-based approach, the residence-based approach, and the activity-space-based approach. The results of this study indicate that the UGCoP and the NEAP exist in the assessment of COVID-19 risk. It concluded that COVID-19 studies need to address the uncertainties due to the UGCoP and the NEAP by considering people's daily mobility. Ignoring peoples' daily mobility and its interactions with the complex and dynamic COVID-19 risk environments may lead to misleading results and misinform government non-pharmaceutical intervention measures.

Using mobile phone data from 10.78 million anonymous phone users in Beijing, Wang et al (2024) compared individual-level residence-based and mobility-based exposure to greenspace. The study observed a significant difference between these two measures, with residence-based exposures having a lower mean value and a greater coefficient of variation. Further, younger and employed individuals and those with larger activity spaces, high visitation diversity, and travel frequency experience a more pronounced NEAP impact.

Cai and Kwan (2024) provided definitive evidence on neighborhood effect averaging as a universal statistical phenomenon of regression to the mean (RTM). This study used a large human mobility dataset of more than 27,000 individuals in the Chicago Metropolitan Area. It provided robust evidence of the existence of the NEAP in a range of individual environmental exposures, including greenspaces, air pollution, healthy food environments, transit accessibility, and crime rates. The study also revealed the social and spatial disparities in the NEAP's influence on individual environmental exposure estimates. Using multi-scenario analyses based on environmental variation and human mobility simulations, the study also revealed that the NEAP is a statistical phenomenon of regression to the mean (RTM) under the constraints of spatial autocorrelation in environmental data. Increasing travel distances and out-of-home durations can intensify and promote the NEAP's impact, particularly for highly dynamic environmental factors like air pollution.

Policy implications of the NEAP

The results of these studies on the NEAP have important implications for all studies on mobility-dependent exposures such as air and noise pollution or traffic congestion. First, due to the existence of the NEAP, accurate assessments of individual mobility-dependent exposures and their health impact require taking people's daily mobility into account; otherwise, assessments of individual exposures may be erroneous. Second, policy-makers should be aware of the effects of neighborhood effect averaging on individual exposures when formulating policy interventions to address the specific needs of disadvantaged social groups: high daily mobility may attenuate people's high exposures in their residential neighborhoods, but low daily mobility would prevent certain socially disadvantaged groups to avoid the high exposures in their residential neighborhoods (Kim and Kwan 2020a,b; Ma et al. 2020). Specifically, it is important to recognize that some social groups may be doubly disadvantaged (e.g., low-income people and women who experience more mobility constraints in their daily lives, which in turn limit their access to jobs and urban opportunities). When these groups live in neighborhoods with high pollution levels, there is little neighborhood effect averaging for them: their limited daily mobility makes it difficult for them to lower their exposures to high pollution levels, as found in Kim and Kwan (2020a,b) and Ma et al. (2020). In this light, these socially disadvantaged groups call for particular attention in public policies.Further, there are some important implications of the NEAP for public health policies. For example, increasing the mobility of those who live in disadvantaged neighborhoods through better, safer, and more reliable public transit, in addition to improving neighborhood quality in situ, may help improve their health outcomes. Further, to mitigate the environmental injustice revealed by the exceptions of the NEAP (i.e., people with low daily mobility or low socioeconomic status), special attention should be paid to the low-mobility vulnerable groups to reduce their hidden environmental risks (Kim and Kwan 2020a,b; Ma et al. 2020).

References

-- Please see the following article for a discussion of the NEAP:Kwan, M.-P. (2018) The neighborhood effect averaging problem (NEAP): An elusive confounder of the neighborhood effect. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 15: 1841.

-- The following recent studies provide strong evidence for the NEAP:

Dewulf, B., T. Neutens, W. Lefebvre, G. Seynaeve, C. Vanpoucke, C. Beckx, and N. van de Weghe (2016) Dynamic assessment of exposure to air pollution using mobile phone data. International Journal of Health Geogrraphics, 15: 14.

Cai, J., and M.-P. Kwan. (2024) The universal neighborhood effect averaging in mobility-dependent environmental exposures. Environmental Science & Technology, 58(45): 20030-20039.

Cai, J., and M.-P. Kwan. (2025) Revealing the complex dynamics of social disparities in personal transit availability considering human mobility and neighborhood effect averaging. Annals of the American Association of Geographers, 115(3): 620-639.

Huang, J., and M.-P. Kwan. (2022) Uncertainties in the assessment of COVID-19 risk: A study of people's exposure to high-risk environments using individual-level activity data. Annals of the American Association of Geographers, 112(4): 968-987.

Kim, J., and M.-P. Kwan (2019) Beyond commuting: Ignoring individuals' activity-travel patterns may lead to inaccurate assessments of their exposure to traffic congestion. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 16(1): 89.

Kim, J., and M.-P. Kwan (2021a) How neighborhood effect averaging may affect assessment of individual exposures to air pollution: A study of ozone exposures in Los Angeles. Annals of the American Association of Geographers, 111(1): 121-140.

Kim, J., and M.-P. Kwan (2021b) Assessment of sociodemographic disparities in environmental exposure might be erroneous due to neighborhood effect averaging: Implications for environmental inequality research. Environmental Research, 195: 110519.

Liu, Y., M.-P. Kwan, L. Song, C. Yu, and Y. Cui (2025) How mobility-based exposure measures may mitigate the underestimation of the association between green space exposures and health. Social Science & Medicine, 379: 118190.

Lu, J., S. Zhou, Z. Zheng, L. Liu, and M.-P. Kwan (2024) Examining the relationship between social context and community attachment through the daily social context averaging effect. Geografiska Annaler B, 106(2): 196-216.

Ma, X., X. Li, M.-P. Kwan, and Y. Chai (2020) Who could not avoid exposure to high levels of residence-based pollution by daily mobility? Evidence of air pollution exposure from the perspective of the neighborhood effect averaging problem (NEAP). International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(4): 1223.

Tan, Y., M.-P. Kwan, and Z. Chen (2020) Examining ethnic exposure through the perspective of the neighborhood effect averaging problem: A case study of Xining, China. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17: 2872.

Wang, J., M.-P Kwan, G. Xiu, X Peng, and Y. Liu (2024) Investigating the neighborhood effect averaging problem (NEAP) in greenspace exposure: A study in Beijing. Landscape and Urban Planning, 243: 104970.

Wang, L., S. Zhou, Z. Zheng, J. Song, J. Lu, and M.-P. Kwan (2025) Unveiling the neighborhood effect averaging problem: The role of daily mobility in shaping built-environment quality exposure. Annals of the American Association of Geographers, online.

Wu, H., and Y. Liu (2026) Individual mobility and heat exposure: Distinguishing residence-based and mobility-based assessments. Environmental Impact Assessment Review, 118: 108292.

Wu, H., G. Zhang, Y. Liu, and Y. Ming (2025) Addressing neighborhood effect averaging problem: Distinguishing mobility-based and residence-based heat exposure. Building and Environment, 280: 113139.

Yu, H., A. Russell, J. Mulholland, and Z. Huang (2018) Using cell phone location to assess misclassification errors in air pollution exposure estimation. Environmental Pollution, 233: 261-266.